Archive files detailing the fate of millions of Soviet citizens who were executed or imprisoned during the Stalin era have suddenly been made harder for historians to access. The Russian federal archive authority’s decision to limit access to such documents to the relatives of individual victims is both a violation of Russian law and will further hamper the work of historians researching the period. As it is, to date just a quarter of Stalin’s victims are known to historians by name.

Last month, Yekaterinburg-based amateur historian Oleg Novosyolov, who has for years been researching Stalin-era repression in regional archives and who runs a Telegram channel called Repression in Sverdlovsk, shared news with his followers that from now on only the relatives of Stalin’s victims would be granted access to their case files.

According to Russian law, once a Stalin-era case has been closed for 75 years, anybody can access its associated files, and yet, according to a Rosarkhiv directive issued to archives, certain documents were reclassified as “official information for limited distribution” on 20 March.

The order means that unclassified documents can be marked “for official use” if their distribution could “pose a potential threat to the interests of the Russian Federation”, though, as Novosyolov wrote, “the wording is so vague and contradicts the law on archival affairs … that some archives took six months to start implementing the changes.”

The co-founder of the Memorial Human Rights Centre, Irina Shcherbakova, told independent radio station Echo that the archives of the former NKVD and KGB, which are run by Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB), were already only allowing relatives of Stalin’s victims access to case files, and that the practice was now being expanded to other archives.

“This isn’t just a ban, of course. It’s another attempt to erase memories of the past under Stalin and to impede academic freedom,” said historian Tamara Eidelman, who added that the effective ban on carrying out historical research would be highly damaging.

The entrance to the FSB building, formerly the KGB building, on Moscow’s Lubyanka Square. Photo: World History Archive / Alamy / Vidapress

Vitaly Pavlov*, a researcher of Stalin-era repression who continues to work in Russia, told Novaya Gazeta Europe that a large number of documents would now be required to gain access to case files.

“They’ll only be issued to people who can prove a familial link. If, say, you need documents about your great-grandfather, you’ll need your birth certificate, those of your parents, and that of your grandparent on which the great-grandfather in question is mentioned,” Pavlov explains.

Currently, however, the topic of Stalinist political terror is not receiving much attention in Russia. “In our region, there are two people looking into repression: me and another woman who I think is a member of Memorial,” Petrov says.

“The country that spawned this repression is afraid to talk about it out loud, so you have to knock on doors yourself to get answers if you want your relative to be anything more than just another anonymous victim.”

“About once a month I’ll run into another local historian at the archive,” Petrov adds. “As a rule, they’re investigating older cases or checking the biographical data of somebody who was persecuted.”

Another Russian researcher, Matvey Leonov*, who, having researched the persecution of his own relatives, is now awaiting a certificate of rehabilitation on their behalf, described his experiences gaining access to the archives.

“At first, I studied my family tree to find out the ethnic background of my ancestors, who they were and where they came from. When you’re a relative who has paperwork and certificates of birth, marriage, death, and baptismal records of every ancestor going back in a straight line, they’ll give you everything. At least for now.”

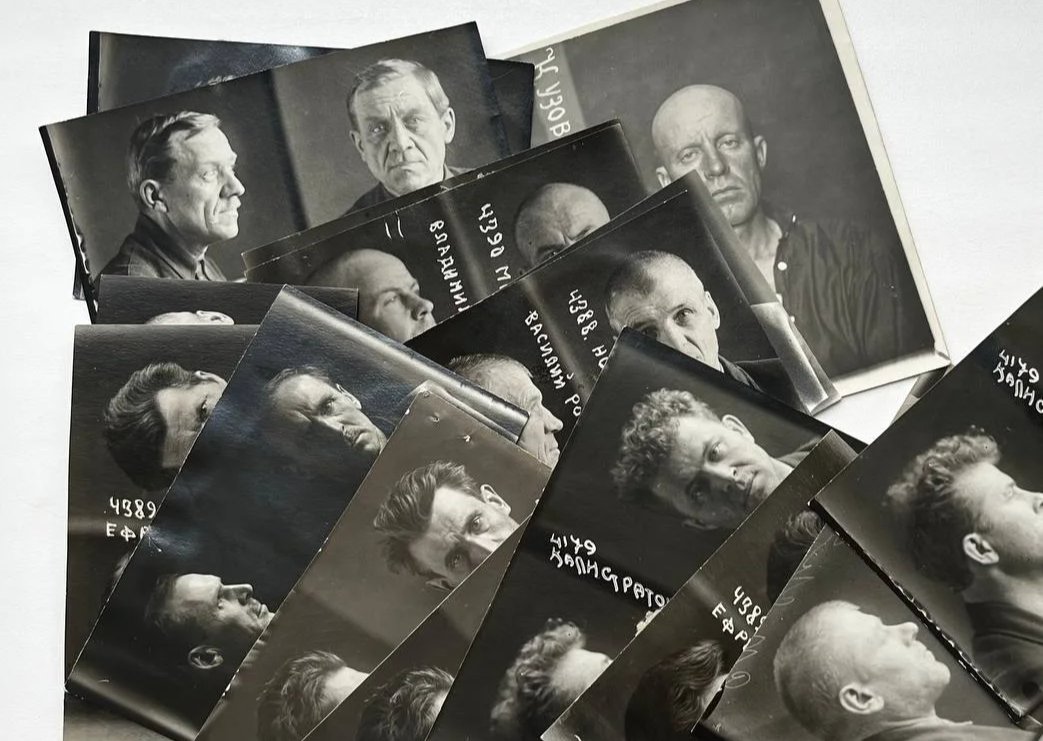

Photos of Stalin-era political prisoners. Photo: Repression in Sverdlovsk / Telegram

“The country that spawned this repression is afraid to talk about it out loud, so you have to knock on doors yourself to get answers if you want your relative to be anything more than just another anonymous victim,” he says.

The unnamed

Following the change of rules, one amateur researcher, Vladimir Redekop, wrote to Rosarkhiv, the Justice Ministry and even the Presidential Administration questioning the new restrictions and published the answers he received.

The President’s Office told Redekop that the decision to limit access had been “dictated primarily by the need to protect Russian interests” in the face of “unfriendly actions against the country” and the need to “protect information” in the archives “from the distortion of historical facts and events, their false interpretation, or use in the interests of unfriendly states and territories.

A list of suspected counter-revolutionaries in the Sverdlovsk region compiled in the late 1920s. Photo: Repression in Sverdlovsk / Telegram

“There are currently about 4.5 million open archival cases containing ‘sensitive information’, the use of which may harm the interests of the Russian Federation,” the Presidential Administration wrote in its response.

According to Memorial, the total number of people persecuted during the Stalin era may be as high as 12 million, and yet most of their names remain unknown, says Andrey Kalinin*, a Russian historian specialising in the period.

“The Rosarkhiv order will have an extremely negative effect on the study of Soviet history. We currently know about a quarter of the names. Some regions have never even published a comprehensive list of local victims! And the state avoids discussing its uncomfortable past,” Kalinin says.

Pavlov says that he believed that the real reason the government decided to restrict access to case files was to make the work of historians who have left Russia more complicated.

“Maybe word got out that the memorial people were still working in some archive or other and sending copies of case files to other academics in Europe.”

“I don’t think that this is specifically aimed at preventing certain facts from being made public, but more of a way to monopolise memory. As if to say, ‘we know how to talk about repression ourselves, and don’t need all these amateur researchers pawing through the archives and then publishing their findings in dubious publications abroad’.”

“Maybe word got out that the memorial people were still working in some archive or other and sending copies of case files to other academics in Europe. Historians living abroad have told those still living in Russia where they can find the most illuminating documents … which were then copied and shared with colleagues abroad for further study,” Pavlov concluded.

*Name changed for security reasons.